In the 19th Century it is well documented that across the west, when science was turning the world around, beliefs in the supernatural rose. Roger Luckhurst writes about the relationship between science and magic: Every scientific and technological advance encouraged a kind of magical thinking and was accompanied by a shadow discourse of the occult (Roger Luckhurst, online)

Ideas of materiality were changing, the revolution of Daguerre's photography made the movement of thought visible and tangible and darkness was in retreat as gaslighting illuminated cities.

It's intriguing to think about Giselle being made in Paris in this context as perhaps strangest of all, in 1840 the dead had begun moving at night through the streets.

Moving the dead

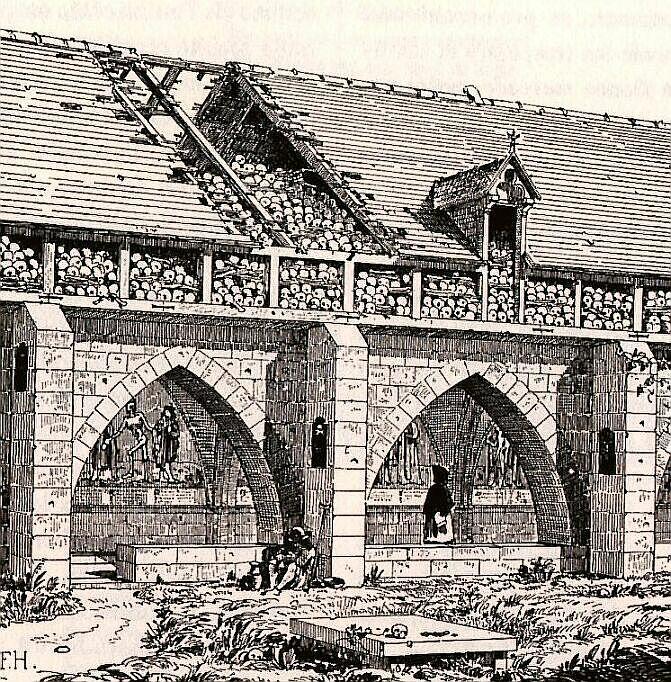

In 1786, following a series of collapses at a mass grave at the overflowing Saint Innocents cemetery, the remains of dead citizens had rolled nightly on black covered wagons for two years. Millions of bones were moved to the catacombs, this story is described in Andrew Miller's Pure. Theophile Gautier will have been aware of the catacombs which in the early 1800s had become a place for concerts and other events.

The removal of bones began once again, a year before Giselle was written.

Return to the weird

Perhaps in Paris specifically, the popularity of the supernatural therefore met a desire not to be thrilled by feeling fear but rather experience something familiar, to double back on the uncanny, and in the words of Mark Fisher make a return to the weird . Following this pathway of thought the dead go back to their own world, in a process not of re-enchantment (Luckhurst) rather they are re-constituted in stories when they might be imagined not as charnel, but as ghosts, and in the case of Giselle, the beautiful Wilis.

empathy and sympathy and slavery

There are other kinds of haunting in Paris during 1841 partly because the cities wealth was built upon slavery. France had been the world’s biggest exporter of sugar, coffee, and cotton, the material used to make Romantic tutus. France was a major colonial power, a key player in the slave trade accruing enormous wealth from transporting and enslaving millions of Africans into French colonies.

The theorisation and materialisation of the body as a territory of state control is part of this colonial history and is discussed at great depth in the work of Susan Leigh Foster who has written extensively on the philosophical, political, and cultural significance of ideas and materiality of bodies. Leigh Foster's investigation of how concepts of sympathy and empathy, including in the writing of the key western philosophers such as David Hume and Adam Smith, developed in parallel with colonisation and the evolution of art and culture including dance and ballet. We could not possibly do justice to her scholarship here but strongly encourage you to explore it yourselves.

A Haunted House

Ghost stories often refer to kinaesthetic sensations in the shock of apprehending and then recognising a ghost These are themes included in one of our collaborators Seke Chimutengwende's project looking at ghosts and haunted houses as a metaphor for how histories of slavery and colonialism haunt the present.

Two worlds?

One departure point for this project was our wish to explore the way we move between online and offline world, mirroring the two acts of Giselle. However is Giselle really so binary? Act 1 might take place in the valley but it is coded to point to the presence of another world and other beings, particularly in the musical score. Alastair Macaulay pointed us to Cunningham's 1993 work Doubletoss resonating with similar of ideas both of two worlds co-existing and Giselle.

A de-centred stage which held multiple spaces was not a new choreographic and philosophical strategy for Cunningham, however Doubletoss, made after the death of Cunningham's partner John Cage, was open to readings around ghosts and loss. Macaulay writes movingly of a later revival: 'Cunningham’s own immediate sense of loss is also a constant subtext, but so is the idea that the dead accompany and inspire us'. (Alastair Macaulay, Cunningham and Cage, Reunited, Restaged,online)

Loss lost

We might also look back to writer William Gibson in No Map for These Territories who in 1999 spoke about cyberspace as no longer something we enter but something all around us. Perhaps the Romantic ballet reminds us of a time when we could look back nostalgically at our social media feeds and how they were haunted by people we once knew, a time when in the words of Mark Fisher loss through digital recall had been lost (Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life, pg 2).

New Dread/True Dread

Today however what we might feel is perhaps more accurately expressed as dread, we have different ghost stories and other kinds of hauntings in the pervasive invisible presence of multi-nationals through their avatars, chatbots and algorithms.